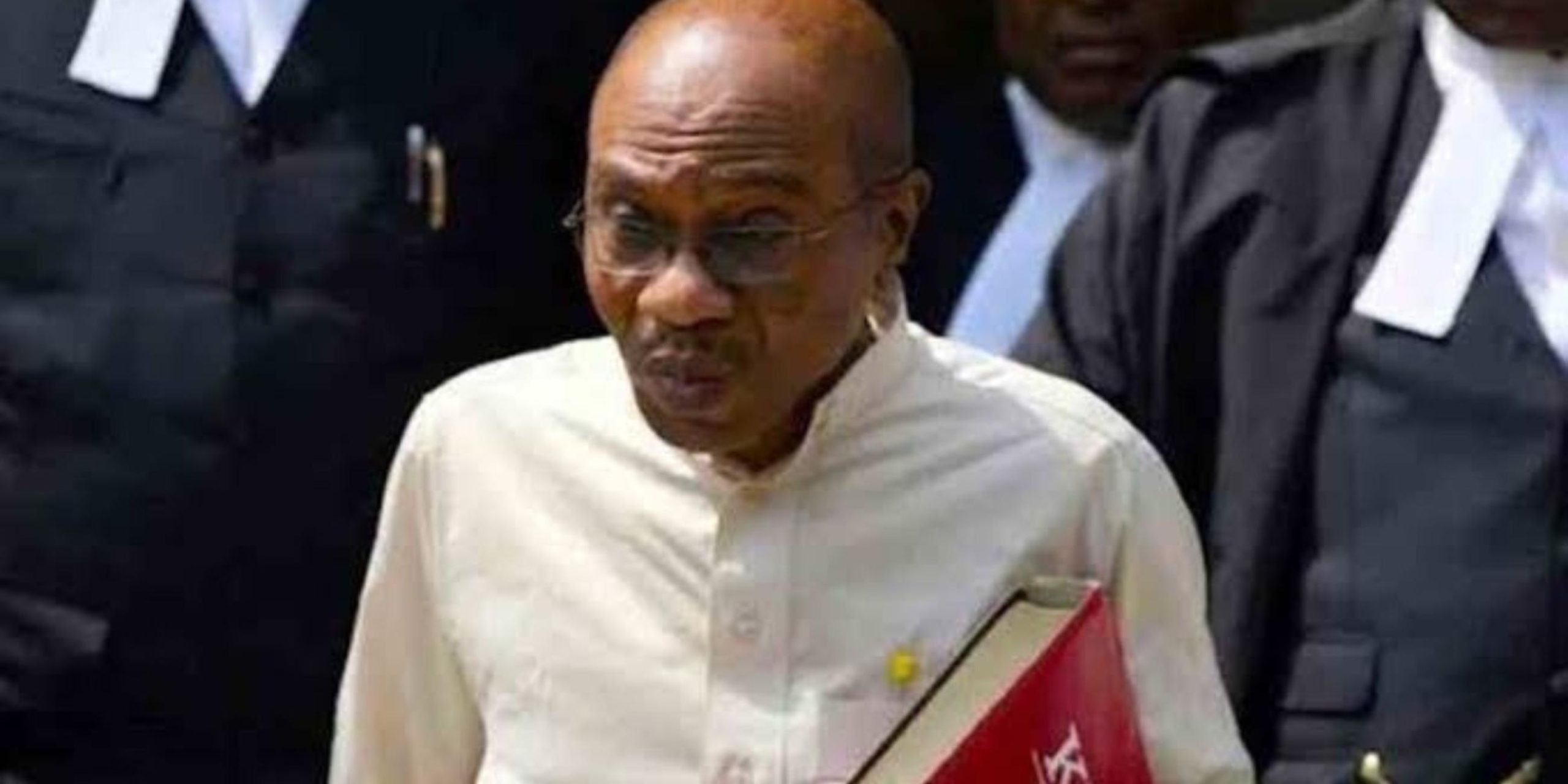

No Proof, No Records”: EFCC Witness Adetola Admits Lack of Evidence in $400,000 Cash Claim Against Ex-CBN Governor Emefiele

In a dramatic and revealing moment at the Special Offences Court in Ikeja, Lagos, on Monday, the trial of the embattled former Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Mr. Godwin Emefiele, took a new turn as the seventh prosecution witness admitted before the court that he had no documentary evidence to support a key allegation in the case.

The witness, John Adetola, who served as the executive assistant to Emefiele, stunned the courtroom when he told Justice Rahman Oshodi that he neither kept receipts nor documented any form of communication—such as call logs or messages—to substantiate his claim that he delivered $400,000 in cash to the former CBN boss in 2018.

With the case hinging on multiple allegations of bribery and unlawful financial transactions amounting to $4.5 billion and ₦2.8 billion, the absence of physical or digital evidence to back such a crucial accusation could represent a potential setback in the prosecution’s effort led by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC).

Adetola’s testimony, while expected to bolster the EFCC’s case against Emefiele and his co-defendant, Henry Omoile, instead raised eyebrows due to its reliance on personal recollection and absence of traceable proof. The 44-year-old witness, who has a Higher National Diploma in Secretarial Studies and is a certified member of the Chartered Institute of Personnel Management, revealed during direct examination that he acted on instructions from another former CBN official, Eric Odoh.

YOU MAY READ

Court to Rule on Emefiele’s Application Alleging Bias, February 26

“In 2018, I can’t remember the exact date, Mr. Eric Odoh sent me a WhatsApp message asking me to collect $400,000 from Mr. John Ayoh [former Director of Information Technology at CBN] and hand it over to the governor in Lagos,” Adetola stated before the court.

He described following the directive by going to Ayoh’s residence in Lekki, collecting an envelope presumed to contain the money, and delivering it to Emefiele in Lagos. However, when pressed by the EFCC lead counsel, Rotimi Oyedepo (SAN), on whether he preserved any evidence of the transaction, the witness repeatedly answered, “I did not see any need for it.”

This assertion was met with visible reactions from the court gallery, prompting murmurs among attendees and legal observers present.

Things grew more intense during cross-examination by Emefiele’s lead counsel, Olalekan Ojo (SAN), who immediately zeroed in on the lack of physical, digital, or even circumstantial evidence supporting Adetola’s claim.

“You never documented this alleged cash transaction in any form—no receipt, no WhatsApp screenshot, no email, no phone call recording?” Ojo queried.

“No, I did not,” Adetola replied.

“You never had any communication directly with Mr. Emefiele about this money, either before or after handing over the envelope?”

“No, I did not,” he admitted.

Ojo further questioned whether Adetola was under any immunity agreement with the EFCC, to which the witness responded in the negative, affirming that he is not facing any charges in relation to the matter. He also said he did not receive any benefit, plea deal, or assurance of non-prosecution from the anti-graft agency.

Perhaps most damning to the credibility of his testimony, Adetola acknowledged that even in his official statement to the EFCC, he made no mention of having discussed the transaction with Emefiele.

This revelation sparked a visibly concerned reaction from Emefiele, who sat in the dock, expressionless but attentive, surrounded by his legal team and security personnel.

YOU MAY READ

Court Orders Final Forfeiture of $2m, Seven Properties Linked to Emefiele

Adetola told the court that he was detained by the EFCC for 11 days during the course of the investigation but said that at no point during his detention was he brought face-to-face with either Emefiele or John Ayoh for a confrontation or clarification regarding the alleged transaction.

“I spent 11 days in EFCC custody, but I was not made to meet or discuss with Mr. Emefiele or Mr. Ayoh during that period,” he said.

Asked whether he was confronted with any supporting or contradictory material while in EFCC custody, Adetola said he was shown some WhatsApp printouts referencing the transaction. However, he maintained that these messages did not include any communication between him and the former CBN governor.

When re-examined by EFCC prosecutor Oyedepo, Adetola maintained his stance, again emphasizing: “I did not see any need to document it.”

This repeated refrain quickly became the defining theme of the day’s proceedings—a troubling mantra that legal observers fear may affect the evidentiary strength of the prosecution’s case.

During his initial testimony, Adetola provided some insight into his role as executive assistant to Emefiele during the latter’s time at the helm of the Central Bank. According to him, his duties included scheduling appointments, coordinating the governor’s personal and professional logistics, and acting as a liaison between Emefiele and other senior CBN staff.

“My direct boss is the first defendant. The first defendant is the head of the secretariat, and I report directly to him,” he clarified in court.

Yet, when asked by the second defendant’s lawyer, Yinka Kotoye (SAN), whether he had any professional or personal dealings with Henry Omoile regarding the alleged cash delivery or any other matter, Adetola flatly denied any association.

“I never dealt with Mr. Omoile in any way connected to this case,” he stated.

YOU MAY READ

EFCC secures largest asset recovery in history: court orders final forfeiture of Abuja estate worth billions of naira, exposed as Godwin Emefiele’s 753 dubplexe

Legal analysts present at the court expressed mixed reactions to Adetola’s testimony. Some saw his account as potentially sincere, albeit poorly documented, while others were more critical, citing the fundamental principles of evidentiary procedure in criminal prosecution.

“It’s not enough to simply say you delivered cash; you must demonstrate it—especially in a trial where the integrity of public institutions and trust in governance is at stake,” said Barrister Femi Olatunji, a Lagos-based criminal justice expert.

Another observer, Ms. Rita Ajibade, a senior research fellow in legal studies at the University of Lagos, added: “This kind of testimony without corroboration could seriously weaken the prosecution’s case. Even if it’s the truth, courts deal with proof, not intuition.”

On social media, the day’s proceedings also sparked vigorous debate. On X (formerly Twitter), the hashtag #EmefieleTrial trended by afternoon, with many Nigerians questioning the seriousness of a federal anti-graft investigation that relies on what some dubbed “hearsay evidence.”

“EFCC needs to do better. This isn’t how you try to nail a man you accuse of stealing billions,” one user wrote.

Another tweeted: “How do you allege a $400k bribe and not keep a receipt, a screenshot, or a recorded call? Even Yahoo boys know better!”

Godwin Emefiele and his co-defendant Henry Omoile are facing a 19-count charge bordering on alleged bribery, corruption, abuse of office, and illicit financial dealings to the tune of $4.5 billion and ₦2.8 billion.

The charges, filed by the EFCC, form part of a broader investigation into Nigeria’s financial institutions and the alleged misuse of public office during Emefiele’s controversial tenure as CBN Governor—a period that saw the naira devaluation, border closure policies, and accusations of reckless foreign exchange allocations.

The trial, which has dragged on for months, is seen as a key litmus test for the Tinubu administration’s promised anti-corruption reforms. It has also become a focal point in the larger debate over financial transparency and institutional integrity in Nigeria.

Justice Rahman Oshodi, who has been firm in overseeing the proceedings, discharged Adetola at the end of his testimony and adjourned the matter to Tuesday, May 28, for the continuation of the trial.

As the case resumes, attention will shift to the next witness and whether more concrete evidence can be introduced to support the charges leveled against Emefiele and his alleged accomplice.

With Adetola’s testimony now part of the trial record, questions remain as to how much weight the court can or will place on his claims—particularly in the absence of verifiable documentation. His role, however, has added a layer of intrigue to a case already marked by political, economic, and legal complexity.

For now, Emefiele continues to maintain his innocence, with his legal team repeatedly emphasizing that no credible evidence has directly tied him to any financial wrongdoing.

Whether the EFCC can ultimately prove its case beyond reasonable doubt remains to be seen. But for many Nigerians, this trial is about more than just one man—it’s about justice, accountability, and the future of institutional trust in a country long plagued by corruption scandals.