The Saints and the Sinners of Nigerian Democracy: A Critical Reflection on Babangida’s Legacy

By Daniel Okonkwo

Nigeria’s political history has been a complex mosaic of military coups, civilian administrations, and democratic struggles. A nation that has faced countless upheavals, Nigeria’s journey toward stable governance is fraught with contradictions—heroes who have shaped the nation’s destiny, and villains whose actions have deepened its wounds. Amidst these turbulent political landscapes, the legacy of General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (IBB) remains one of the most controversial and contentious chapters. A man who, for many, represents both the saint and the sinner in Nigeria’s evolving democracy.

Babangida’s rule, spanning from 1985 to 1993, was marked by a combination of military authoritarianism, economic reforms, and political maneuvering that left an indelible mark on the country. However, the pivotal moment of his leadership—the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election—remains the subject of fierce debate. In the wake of his recent autobiography, A Journey in Service, and the subsequent revelations about his role in key historical events, Nigerians are left grappling with a fundamental question: Can a man whose decisions led to some of the most tragic episodes in the nation’s history ever be considered a reformer?

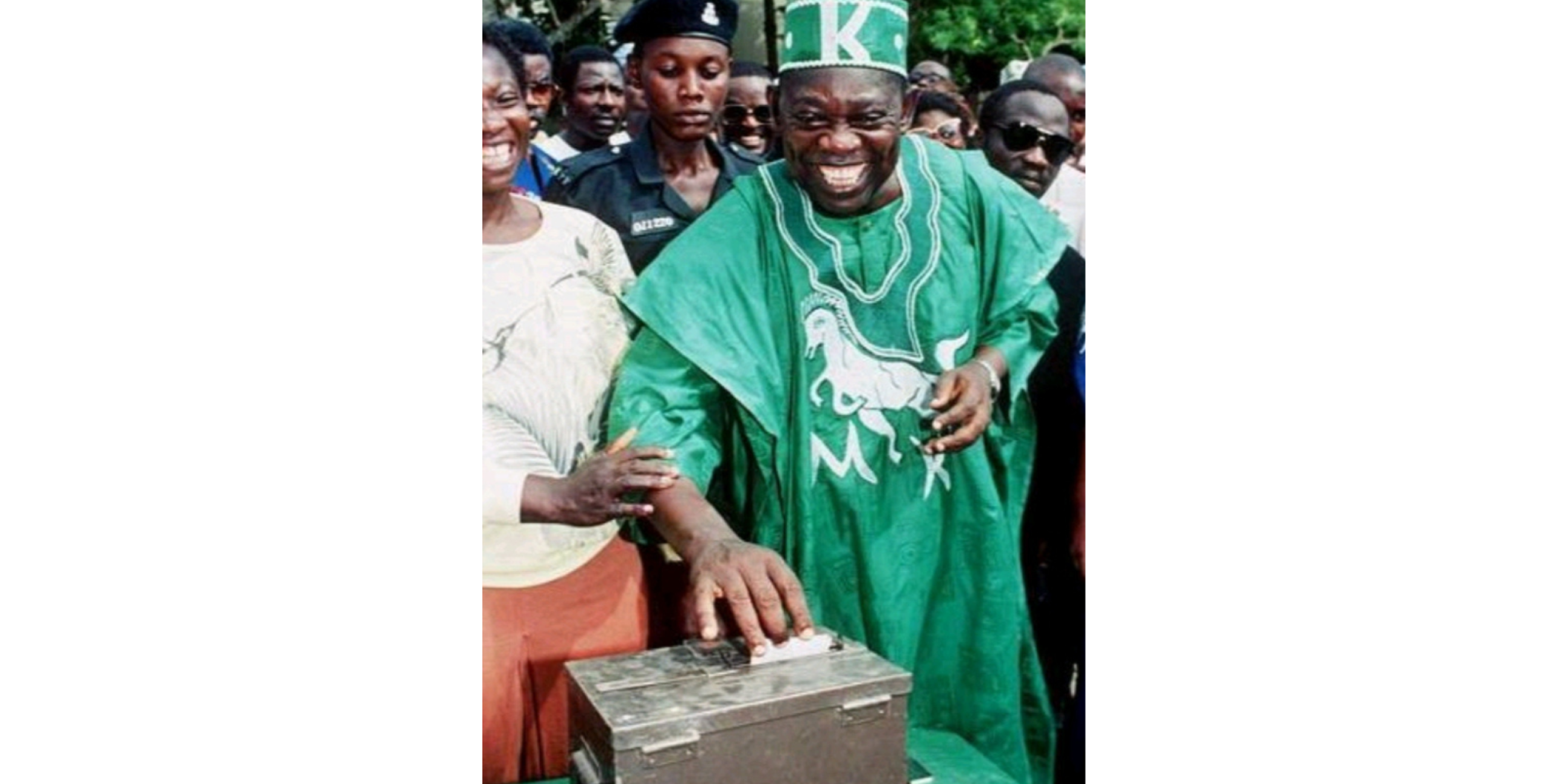

The June 12, 1993, election stands as one of the most significant milestones in Nigeria’s political history. Widely regarded as the freest and fairest election ever held in the country, it was a beacon of hope for Nigerians who had long suffered under the weight of military dictatorship. The election saw the emergence of Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola as the clear winner, a businessman and philanthropist who had garnered broad support across the country.

However, Babangida’s regime, which had been in power since 1985, shocked the nation by annulling the election results, citing vague national security concerns. Babangida’s government claimed that allowing Abiola to take office could lead to destabilization and even civil war. This decision, which is still regarded as a monumental betrayal of the people’s will, led to widespread protests, political turmoil, and eventually the military junta’s exit from power.

In his autobiography, Babangida finally admitted what had long been known—that MKO Abiola had, in fact, won the election. However, Babangida framed the annulment as an “accident of history,” suggesting that his actions were motivated by the desire to prevent violence and chaos in the country. He argued that the powerful forces opposed to Abiola’s presidency—particularly those within the military and political elite—would not allow him to assume office without sparking a violent conflict.

While Babangida’s acknowledgment of the election’s legitimacy comes after decades of silence, his reasoning for the annulment fails to provide the closure that Nigerians have long sought. His admission, though significant, feels hollow to many who view it as a convenient attempt to rewrite history. Babangida’s explanation does little to erase the pain and disillusionment that the annulment caused, especially considering the ongoing injustice that Abiola and his supporters faced after the election. For many, Babangida’s words are “medicine after death”—a late recognition of wrongs that cannot be undone.

Babangida’s tenure is characterized by a mixture of political strategizing and controversial decisions that have made him a deeply polarizing figure in Nigeria’s political landscape. On one hand, he is credited with initiating important economic reforms, including structural adjustment programs that aimed to address Nigeria’s economic stagnation. His administration also laid the groundwork for the eventual return to civilian rule in 1999, a move that some argue was a necessary step for the country’s transition to democracy.

However, these reformist efforts have been overshadowed by Babangida’s blatant disregard for democratic principles. His annulment of the June 12 election, which was regarded by many as a direct violation of the people’s will, forever stained his reputation. In an environment where the rule of law and democratic integrity were already tenuous, Babangida’s actions exacerbated Nigeria’s democratic crisis.

Moreover, Babangida’s human rights record continues to haunt his legacy. His government was marked by widespread censorship, the suppression of dissent, and the arbitrary arrest and detention of political opponents. Perhaps most notably, Babangida’s regime was implicated in the assassination of prominent journalist Dele Giwa, the editor of Newswatch magazine, who was killed in 1986 by a parcel bomb. The assassination remains one of the darkest moments in Nigerian journalism and has led many to question Babangida’s complicity in the murder, despite his repeated denials.

The failure of Babangida’s regime to conduct a transparent investigation into Giwa’s death has left Nigerians with lingering suspicions about the military government’s role in the journalist’s demise. While Babangida has maintained that he hopes the mystery of Giwa’s assassination will one day be solved, the lack of accountability has only deepened the scars of this tragedy.

One of the most revealing sections of Babangida’s autobiography concerns his relationship with General Sani Abacha, the man who succeeded him as military head of state. Babangida reflects on how Abacha, who played a key role in the 1985 coup that brought him to power, ultimately turned against him. Abacha, a man who had saved Babangida’s life on several occasions, became increasingly antagonistic toward the idea of civilian rule and Abiola’s presidency.

Babangida’s revelations about Abacha’s plots to overthrow him, despite their long-standing relationship, add complexity to the narrative of power struggles that shaped Nigeria’s political landscape in the 1990s. Abacha, known for his ruthless and authoritarian rule, would eventually seize power in 1993, after Babangida was forced to step down in the wake of the June 12 crisis. Babangida’s account sheds light on the internal dynamics within the military that shaped the country’s political trajectory during this turbulent period.

While Babangida’s admission that Abacha harbored animosity toward Abiola and actively worked against the peaceful transition to civilian rule is an important piece of the puzzle, it also highlights the deep fractures within Nigeria’s military leadership. The revelation also underscores how Nigeria’s political elites have often put personal ambitions and power struggles ahead of the welfare of the Nigerian people, contributing to the nation’s ongoing struggles with democratic consolidation.

The question of what to do with Babangida’s legacy is one that continues to divide Nigerians. Some view him as a statesman who tried to navigate the country through difficult circumstances, while others see him as a dictator who failed to live up to the promises of democracy and human rights. Despite his recent admissions of wrongdoings, Babangida’s legacy remains a source of bitter contention for many Nigerians.

For those who suffered directly under his regime—whether through the annulment of the June 12 election, the oppression of dissent, or the assassination of Dele Giwa—the idea of forgiving Babangida for his actions is a difficult one. For them, the scars of history cannot be erased by mere words. Babangida’s role in the subversion of democracy remains a profound stain on Nigeria’s journey to democratic maturity.

At the same time, Babangida’s recent autobiography provides an opportunity for Nigerians to reflect on the importance of historical accountability. While his actions may never be fully forgiven, his willingness to finally admit to some of the most controversial aspects of his rule is an important step in the process of national healing. For the Nigerian people, acknowledging past wrongs is a crucial step toward building a more just and democratic society.

In the grand narrative of Nigerian democracy, Babangida occupies a paradoxical space. He is a figure who represents both the sinner—due to his role in the annulment of the June 12 election, his human rights abuses, and his political machinations—and, to a lesser extent, the saint, for his role in economic liberalization and the eventual return to civilian rule. The true saints of Nigerian democracy, however, are those who fought for the people’s will, risked their lives to uphold democratic principles, and made sacrifices in the face of oppression.

As Nigeria continues to grapple with the legacy of its past, the lessons of June 12, 1993, and the broader history of military rule remain fresh. The pursuit of justice for those wronged by Babangida’s regime and others like him is an ongoing struggle. The ghosts of past injustices serve as a reminder that democracy, once stolen, takes generations to restore.

Babangida’s autobiography, A Journey in Service, provides important insights into Nigeria’s turbulent past, but it is not a panacea for the pain and disillusionment that many still feel. His reflections, though significant, underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting Nigeria’s hard-earned democracy. The line between saints and sinners in Nigerian politics remains blurred, and the struggle for true democracy continues.

EXCERPT

The Saint And The Sinners Of Nigerian Democracy By Daniel Okonkwo

In his autobiography, Babangida finally admitted that Abiola won the election, acknowledging the annulment as an “accident of history.”

Nigerians have endured a complex and often turbulent governance history, oscillating between military rule and civilian administrations.

Among these, one administration stands out in its controversial legacy: the regime of General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (IBB). His leadership remains a defining yet contentious period in Nigerian history, characterized by political maneuvering, military dictatorship, and a mixture of progressive and regressive decisions. Despite decades of silence, Babangida recently revisited these events in his autobiography, A Journey in Service, officially launched at the Transcorp Hilton Hotel, Abuja, in the presence of President Bola Tinubu and other dignitaries. The event also doubled as a fundraiser for the IBB Presidential Library.

For over 32 years, Babangida remained largely silent on one of the most defining moments of his rule—the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election. Widely regarded as Nigeria’s freest and fairest election, it was won by Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola.

However, Babangida’s military government abruptly annulled the results, citing national security concerns. The decision ignited widespread protests and political unrest, eventually forcing him to step down.

In his autobiography, Babangida finally admitted that Abiola won the election, acknowledging the annulment as an “accident of history.”

He claimed his primary concern was preventing Abiola’s assassination by powerful forces opposed to his presidency. According to Babangida, allowing Abiola to assume office could have led to a second civil war. While he conceded that annulling the election was a subversion of the people’s will, his rationale does little to assuage the pain and disillusionment that followed.

His admission drew strong reactions from various individuals and pro-democracy groups, including Afenifere, the Coalition of Northern Groups, Segun Osoba, Mike Ozekhome (SAN), Omoyele Sowore, Profile International Human Rights Advocate, and other prominent Nigerians. Many viewed his remorse as too little, too late—an attempt at historical revisionism rather than genuine contrition.

Another dark chapter of Babangida’s regime is the assassination of journalist Dele Giwa of Newswatch magazine. Giwa was killed in 1986 by a parcel bomb, a method of assassination unprecedented in Nigeria. Suspicion immediately fell on the military government, as Giwa had been investigating sensitive national security issues. Babangida continues to deny involvement, asserting that he hopes the mystery surrounding Giwa’s murder will one day be solved. However, critics argue that the government’s failure to conduct a transparent investigation has only deepened suspicions.

Babangida also detailed his complicated relationship with General Sani Abacha, who ultimately succeeded him. While acknowledging that Abacha once saved his life and played a key role in the 1985 coup that brought him to power, Babangida described him as a complex character.

According to A Journey in Service, Abacha harbored deep animosity toward Abiola and actively worked against his presidency. Babangida revealed that Abacha had even plotted a coup against him, despite their longstanding friendship. This revelation sheds light on the internal power struggles that shaped Nigeria’s political trajectory in the 1990s.

Despite his regrets and explanations, Babangida’s actions continue to cast a long shadow over Nigeria’s democratic journey. While he played a role in Nigeria’s economic liberalization and initiated structural reforms, his legacy remains tainted by the annulment of the June 12 election and his regime’s human rights abuses. His recent admissions raise an important question: What should Nigerians do with this information?

For many, Babangida’s reflections are “medicine after death.” The damage inflicted by his decisions cannot be undone by mere words. However, his admissions serve as a reminder of Nigeria’s turbulent past and the importance of democratic integrity. His autobiography, A Journey in Service, provides insights into the machinations of power but also highlights the need for historical accountability.

In the annals of Nigerian democracy, Babangida remains a paradox—a leader who claimed to act in the nation’s best interest but whose actions often led to national crises. His regime’s decisions affected millions of Nigerians, some of whom still await justice.

The true saints of Nigerian democracy are those who fought for the people’s will, risking their lives to uphold democratic principles. The sinners, on the other hand, are those who subverted democracy for personal or political gain. Babangida’s reflections, though significant, do not absolve him of responsibility. Instead, they reinforce the need for continued vigilance in protecting Nigeria’s hard-earned democracy.

As Nigeria moves forward, the lessons of the past must not be forgotten. The ghosts of June 12 and other unresolved injustices serve as a cautionary tale: democracy, once stolen, takes generations to restore. Babangida’s story is not just his own—it is a reflection of Nigeria’s political evolution, where the line between saints and sinners remains blurred.

Source: SR