G#nmen Kidnap Anglican Priest and His Wife

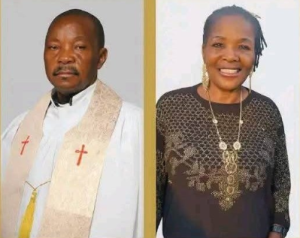

On the early hours of Tuesday, October 28, 2025, g#nmen believed to be kidnappers abducted an Anglican cleric and his wife in Kaduna State, throwing their family, parish and community into a state of shock and urgent prayer. The couple — identified by family and church sources as Ven. Edwin Achi and his wife, Sarah Achi — had only recently moved into a new property when assailants entered and took them away, according to family messages shared publicly and local reporting.

For residents of Kaduna, where attacks on clergy and mass abductions have become a recurring and deadly feature of the security landscape, the story is painfully familiar. Yet each new case exposes fresh fractures: lapses in local intelligence, the ease with which criminals identify targets using community information, and the spiralling sense of vulnerability that has replaced what were once inviolable social spaces — homes and places of worship.

This long-form report reconstructs the known facts, places the abduction within Kaduna’s broader security trajectory, follows the immediate operational response, captures the rhythms of family grief and church mobilisation, and outlines the wider national implications of attacks on religious leaders.

Family messages that circulated on social media and through local contacts reveal the outline of what happened: in the very early hours of October 28, masked gunmen descended on the new residence of the Achi family. They forced entry, overwhelmed any household resistance, and took both the cleric and his wife. A family member named Avril — who posted an account of the incident on social media — said the couple had recently moved into the property, and suggested their newness in the neighbourhood may have made them vulnerable.

The Diocese of Kaduna, Anglican Communion, quickly released a communiqué confirming the abduction and calling on members and well-wishers to pray for the safe and swift release of Ven. Achi and his wife. The statement, while brief, underscored the church’s fear that the incident could escalate into a longer hostage crisis if not handled with urgency and discretion.

Local posts, eyewitness commentary and community channels further corroborated the time and place of the attack. Although police or state authorities had not, at the time of those initial reports, released a detailed official account, the convergence of family confirmation and diocesan notice created an early, credible picture: a targeted abduction of a clergy household in the heart of Kaduna State.

To understand why a priest and his wife could be seized in this way, we must look at the shifting calculus of kidnapping in northern and central Nigeria. Over the past half-decade, abduction tactics have evolved from opportunistic snatches along highways to sophisticated operations against residences, schools, marketplaces and — increasingly — religious figures. Clergy are targeted for several reasons:

- Perceived Wealth and Ransom Capacity

Religious leaders are often believed — rightly or wrongly — to have access to communal resources, donation streams, and networks capable of raising ransoms. Churches and religious organisations, especially those with active congregations and diaspora supporters, are viewed as potential sources of large sums. Kidnappers exploit that perception in their targeting logic. - Symbolic Leverage

Abducting a cleric carries symbolic weight. It creates fear that reverberates beyond a single family — shaking congregations, intimidating local networks, and attracting national attention that kidnappers exploit to drive up ransom demands. - Community Intelligence and Pointers

New residents, recent property moves and visible activity can act as inadvertent “pointers” to criminals who rely on local informants or casual observation. As Avril’s message suggested, the fact that the Achi couple had recently moved may have made them easier to locate. Criminal groups use a patchwork of paid informants, petty criminals and social media-scraped data to identify softer targets

The Diocese’s call to prayer was accompanied by frantic phone calls, grassroots mobilisation, and the first stirrings of a typical but fragile communal response: neighbours searching for clues, relatives contacting local police, and church leaders reaching out to security services. The Diocese urged calm and restraint — a standard posture designed to channel panic into coordinated action and to prevent rash attempts at vigilante rescue that dangerously escalate violence.

In a country where the security architecture is often overstretched, family-led negotiations and informal mediators still play a central role in resolving kidnappings. But clergy abductions complicate that dynamic: mediators must balance the desire to secure release with the risk that public appeals or aggressive negotiations will harden kidnappers’ resolve or drive up ransom demands.

Community reaction in Kaduna mirrored these dilemmas. Some residents called for heightened local patrols and coordination with police; others publicly expressed outrage, drawing attention to the repeated pattern of attacks that have left many communities exhausted and distrustful of official protection.

At the time of initial reporting, there was no comprehensive public statement from the Kaduna State Police Command detailing the operational response. Historically, however, such incidents prompt a layered security mobilisation: local police begin the initial investigation, state-level tactical squads are deployed for intelligence gathering, and military or paramilitary units (where necessary) are asked to provide logistical and tactical support in rural kidnappings.

Two chronic problems affect the efficacy of such responses in Kaduna and similar states:

- Delay and Fragmentation: Valuable time is lost when local units must await reinforcements or when jurisdictional confusion delays action. Kidnappers exploit these windows to move captives quickly across borders or into dense terrain.

- Intelligence Leakages and Community Mistrust: Effective rescues require local cooperation. But decades of mistrust, and fears of reprisal, often make communities reluctant to provide timely intelligence.

Reports around this incident emphasised the Diocese’s wish for discretion; church leaders often prefer negotiated resolutions to public, force-led rescues that risk retribution. At the same time, families demand results and transparency — a tension that shapes every clerical abduction case.

Kaduna State is not new to the pattern of kidnappings and targeted attacks. Over recent years the state has experienced a mix of banditry, community clashes and organised criminality that overlaps with broader national insecurity trends. That pattern includes attacks on clergy and religious institutions — both Christian and Muslim — underscoring that violence in Kaduna is not motivated solely by sectarian lines but by criminal economies and, at times, political fault lines.

Earlier in 2025 and the preceding years, multiple high-profile abductions in the state and neighbouring areas drew national attention and prompted a spate of short-term security directives — curfews, joint task forces and enhanced patrols. While those measures sometimes yielded quick arrests and recoveries, the systemic drivers—poverty, weak governance in certain localities, porous borders and criminal syndicates—remain largely unaddressed. Scholarly and NGO reports have consistently highlighted the need for a durable, multi-dimensional strategy that combines policing with socio-economic interventions.

For the Achi family, public messages were brief, raw and immediate. Avril’s confirmation on social media — a terse mixture of disbelief and warning about “community informants/pointers for kidnappers” — crystallised the family’s fear. Community members rallied to offer practical support while urging authorities to prioritise the couple’s safe release.

Clergy kidnappings create a second-order trauma for church communities. Congregations must reconcile the immediate spiritual panic with organisational needs: who will lead services, how to provide pastoral support to the family, and how to continue church activities without exposing others to risk. In many cases, local congregations and national religious bodies quietly coordinate with security services and trusted mediators to de-escalate situations and secure release.

In Nigeria’s kidnapping economy, informal negotiators and community elders often play decisive roles. These individuals — sometimes former militants, respected elders, or local power-brokers — are valued for their ability to reach criminal networks, interpret ransom demands, and broker a release without inflaming the situation. Church bodies typically prefer mediators who can operate discretely and insist on verifying any claims or demands.

However, the reliance on such mediators is a double-edged sword: while they have secured release in many cases, their involvement can also normalise ransom payments, inadvertently perpetuating the criminal market. For clerical abductions, religious leaders generally advocate for careful, accountable use of mediators to avoid financing further violence.

This abduction matters because it sits at the intersection of several dangerous trends:

- Escalation of Victim Profiles: Criminals are moving from high-risk public targets to domestic abductions, including clergy homes. This evolution marks a shift in operational audacity and access.

- Information Vulnerability: The role of “community pointers” highlights how social and digital visibility—recent moves, new property, social posts—can be weaponised against residents.

- Potential for Broader Instability: Attacks on religious figures risk inflaming communal tensions, particularly if perceptions of unfair or slow responses spread. Church communities are social anchors; undermining them can have knock-on effects on local cohesion.

Given the immediate risks, a set of pragmatic response measures should be activated:

- Discrete Liaison Team: The Diocese should appoint a small, confidential liaison team to work directly with security forces and trusted mediators, limiting public disclosures that could jeopardise negotiations.

- Community Watch and Rapid Reporting: Local neighbourhoods should be organised into rapid reporting cells with a direct line to police so suspicious movements are reported early.

- Protection for Clergy Residences: Until the crisis passes, temporary security arrangements — guarded arrivals, restricted visibility of addresses, and community patrols — reduce repeat vulnerability.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Inform parishioners about the risks of sharing precise residential details online and urge discretion regarding new moves.

- Coordination with State Security: The Diocese should insist on regular briefings from Kaduna State’s security apparatus, ensuring transparency and prompt deployment where necessary.

At the policy level, the pursuing of kidnappers must be matched by preventive investments: community policing, improved rural infrastructure that reduces bandit movement, and targeted socio-economic programmes in high-risk localities. For religious institutions, internal protocols for security — including vetting, confidential relocation procedures, and emergency funds — could make the difference between a narrow scare and a prolonged crisis.

The federal government, civil society and international partners must also prioritise knowledge sharing: mapping kidnap rings, tracking ransom flows, and coordinating cross-border policing where captors move victims beyond state lines.

Neighbours, church members and community leaders interviewed in the immediate fallout expressed a mix of fear, anger and stoic prayer. Many recalled past cases where kidnappings ended in ransom-fuelled rescues or, tragically, in death. Each recollection reinforced a bitter truth: when criminal networks perceive impunity, they become bolder.

A local elder commented, “They come in the night because they know we will be slower than them. If someone had been watching, maybe this could have been prevented.” Another parishioner said, “The priest has always been a voice of calm here. That he should be taken like this — it is an attack on our little peace.”

Attacks on clergy strike at the heart of civic life. They are assaults on institutions that provide moral guidance, social services and community cohesion. Beyond immediate rescue efforts, such cases invite a national conversation: how should the state redefine protection for frontline community figures? What responsibility do religious organisations have to adapt their operations to a more dangerous environment? And crucially, how does society ensure that a culture of ransom and impunity does not consolidate into a permanent criminal economy?

These questions are not abstract. Every failed prevention, every slow response, strengthens the calculus of criminals and weakens the social fabric that keeps communities resilient.

As this report is written, the Diocese’s prayer calls continue and family members wait in a strange limbo — hoping for a call, a sighting, any sign that the couple will be returned safely. Kaduna’s security services face a test: to respond quickly, transparently, and with the tactical precision that such situations demand.

For now, public facts are limited: the names, the date, the diocesan confirmation and the community alarm. These are enough to launch coordinated action — and they are the foundation for the deeper reporting that must follow when authorities declassify investigation details.

The abduction of Ven. Edwin Achi and his wife is more than a criminal incident. It is a moral emergency for a state that must reconcile daily religious life with the reality of violent predation. How authorities and communities respond will determine whether this becomes another statistic — or a turning point that forces practical change.